When contemplating Barbados’ water resources, the notion of water scarcity is often brought up. Rather than focusing solely on scarcity, it is more constructive to consider how effectively we are managing the water resources that we have. However, we first need to understand the context and challenges Barbados’ water resources and supplies face.

Reflecting on the past

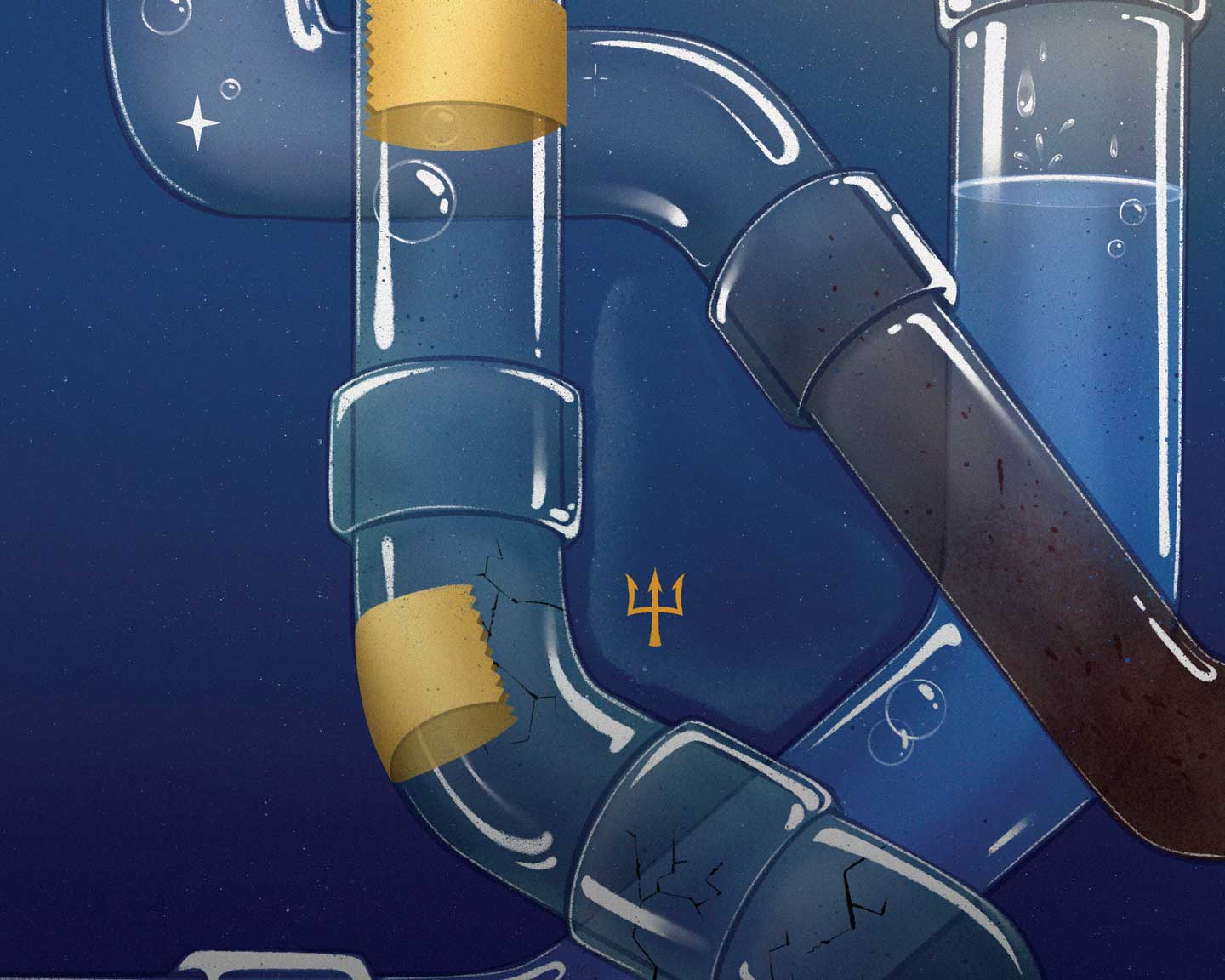

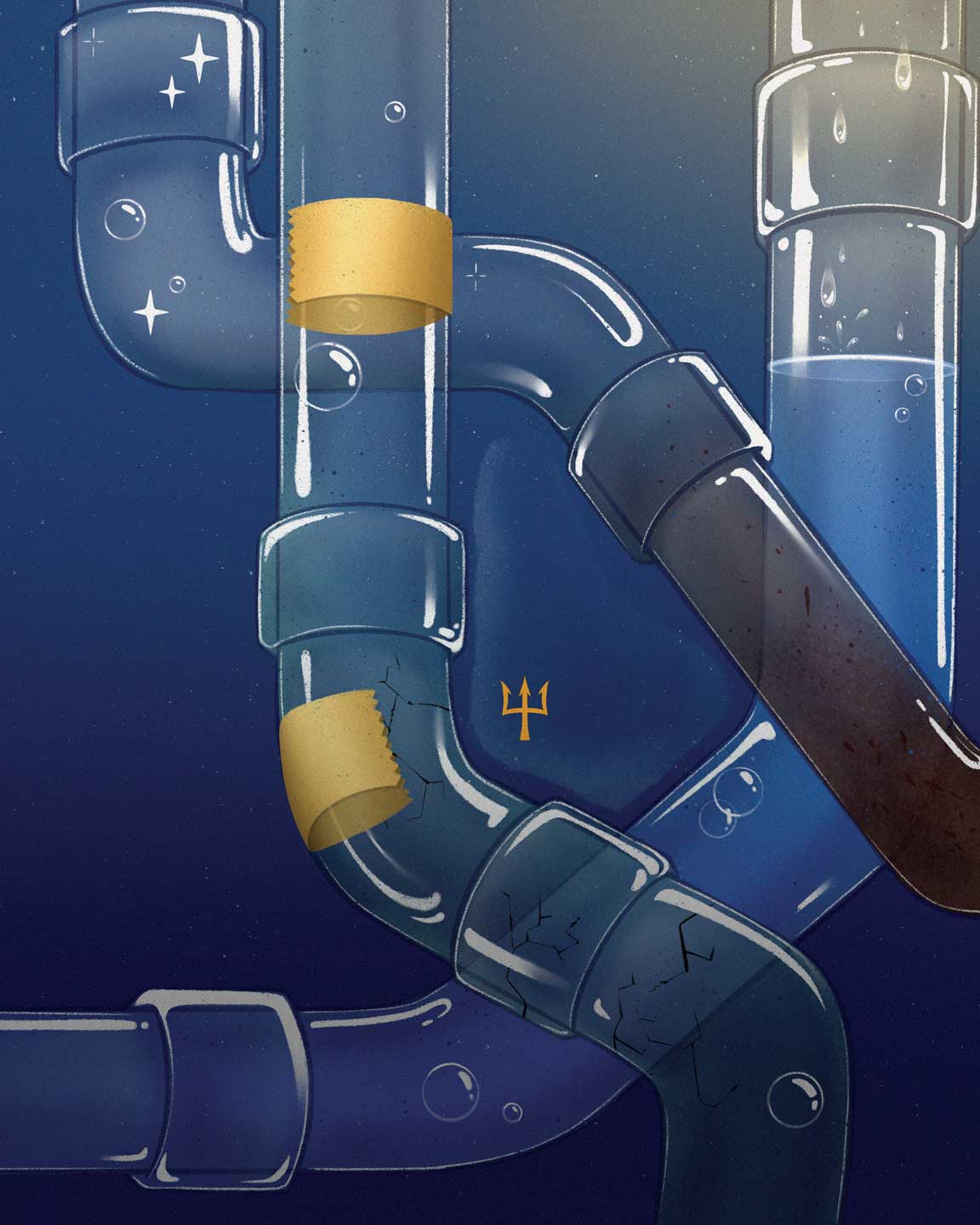

Barbados faces two overarching water-related challenges: institutional and climate change. On the institutional side issues encompass laws, regulations and organisations designed to address these challenges effectively. Over the years, the Barbados Water Authority (BWA) has come in for criticism over its management and stewardship of the water sector. Problems such as ageing infrastructure, equipment breakdowns, sewage in the streets, and high levels of water lost from leaking and burst pipelines were signs of mismanagement, inadequate forward planning and underinvestment. However, responsibility doesn’t rest solely with BWA; past governments have failed to prioritise and invest adequately. Reluctance to adjust tariffs to fund operation, maintenance and investment, and inertia in implementing measures to drive efficiency and effectiveness have exacerbated the issues. Additionally, the consumer – you and I – has contributed to the problem by having one of the highest per person water consumption rates in the Caribbean, by polluting groundwater by dumping garbage in the gullies, private water abstractors unwilling to provide information on their water usage, and by taking the services provided for granted.

Moreover, climate change poses a looming threat, which if the institutional challenges are not addressed, will lead to a situation we just do not want to contemplate. Projections indicate continuing increases in temperatures, more prolonged dry spells, and altered rainfall patterns resulting in more intense rainfall events, which means more runoff, and reduced infiltration. Over time these changes will reduce the volume of water that can be safely abstracted from our aquifers. While estimates of the reduction vary, it could be as high as a 50%. The effects will be felt by farmers, by hotels, by businesses and by households in the form of higher costs and reduced water availability, unless proactive measures are taken.

Flowing forward

Fortunately, there is good news. A lot is being done to tackle the issues and initiate positive change. While Barbados has little control over the direction of climate change, it can adapt to address and mitigate its effects. At the institutional level much has been implemented to better equip the country to confront these challenges outlined.

The Water Reuse Act (2022) provides the legal and regulatory framework for the treatment and reuse of wastewater Simultaneously, measures are being developed to provide financial support to encourage the uptake of wastewater reuse whether for commercial, agricultural or other purposes. This initiative is part of the country’s participation in the CReW+, an integrated approach to water and wastewater management in the Wider Caribbean Region project. The government is investing in upgrading two of its wastewater treatment works, ensuring that treated wastewater meets the standards for reuse. The investments include infrastructure necessary to deliver treated water to where it will be used by farmers, and for managed aquifer recharge when not used for irrigation. Given that between 70 and 80% of consumed water becomes wastewater, the potential for reuse to alleviate climate-induced scarcity is substantial.

A valid question is where will this funding come from? And whether it will burden taxpayers. The good news is that funding has been secured from a mix of sources, including grant funding from the Green Climate Fund for climate adaptation and mitigation measure. Additionally, a Debt-for-Nature swop with the Inter-American Development Bank, the European Investment Bank, and the Green Climate Fund which means that this funding will not increase the country’s debt.

The recently proposed amendment to the Barbados Water Authority Act highlights two coming changes. Firstly, it formalises the proposed adjustment to groundwater protection areas outlined in the 2020 Green Paper. Secondly, and interestingly, is the change in title for the leader of the BWA from General Manager to Chief Executive Officer. I think we can expect to see BWA exploring organisational changes to make it a more agile organisation suitable for the 21st century, not just for today, but looking ahead to the future. Transformation would enable the Authority to capitalise on several ongoing initiatives, including measures to enhance water use efficiency, reducing the amount of water used by households and businesses without compromising performance. These include the promotion of household storage tanks as a resilience measure during emergencies and the establishment of a Water Review Management Committee to specifically address groundwater license and abstraction issues.

Another pressing concern has been the high levels of water losses due to bursts and leakages. Efforts to reduce these water losses are essential not only for conserving groundwater but also for cutting operational costs and greenhouse gas emissions. Ongoing investments in pipeline replacements, active measures to reduce losses, and research into the climate factors affecting burst behaviour are all starting to yield results. It’s important to note that reducing losses is a long-term endeavour with results that are not immediately evident. Reducing losses plays a crucial role in countering the effects of climate change on groundwater availability.

Future flows

Barbados has made addressing its water woes a top political and operational priority. Measures have been taken to increase water reservoir capacity with resilience against hurricanes, pump stations have been equipped with back-up generators, renewable energy systems are being put in place with energy savings being used to fund infrastructure improvements, and water losses are being tackled through pipeline replacement programmes and nonrevenue water loss management systems. Concurrently, efforts to reduce excessive water consumption are underway. The potential for increased reuse of treated pre-owned (waste) water underscores the commitment to invest in the country’s invaluable water resources to ensure security of supply and support for longterm economic development.